Experience | Expertise

Experience | Expertise

Patents protect side hustlers and startups from copycats while boosting investor trust. Learn the basics of provisional vs. full patents, costs, risks, and strategies for...

Startup accelerators move fast—but should you file patents or trademarks before demo day? Learn when to secure IP, how investors view filings, and the risks...

Patents turn fragile startup ideas into defendable assets. Learn how patents protect against copycats, attract investors, enable global expansion, and drive real-world success in competitive...

Utility patents protect how something works. Design patents guard how it looks. This article explores both, from history to real-world cases, and shows why combining...

Patent trolls are like zombies, draining startups with lawsuits. Learn how to defend your innovation with legal strategies, invalidity challenges, PR tactics, and collective action...

Patenting is costly, but side hustlers can protect their inventions strategically. Learn how to cut costs, use provisional applications, and tap into licensing and pro...

Patenting AI and machine learning protects innovation, attracts investors, and turns algorithms into assets. Learn the history, risks, strategies, and cases shaping today’s patent race...

Patent searches save inventors from rejection, lawsuits, and wasted money. Learn how AI speeds the process, what it misses, and why human expertise remains essential.

Patents aren’t just for big corporations. From affordability to global protection, this article busts common myths and shows startups how patents fuel growth, secure investments,...

Patenting your side hustle idea doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Learn how to protect your innovation, choose the right patent type, and avoid burnout while...

Filing a provisional patent application gives inventors 12 months of “patent pending” protection. Discover how it boosts credibility, attracts investors, and buys you time to...

Should your patents and trademarks be owned by you or your business? The answer is clear: entity ownership protects liability, attracts investors, and ensures smoother...

Avoiding patent mistakes can mean the difference between protecting your idea and losing it forever. Learn how to dodge rookie errors—from missed deadlines to weak...

Patents are startup moats that secure innovations, attract investors, and fuel growth. Learn how strategic filing, portfolio expansion, and licensing can transform fragile ideas into...

International patents are the passport your invention needs to travel safely. Learn how startups and side hustles can use PCT, Paris Convention, and smart filing...

Patents are the armor and amplifier for startups, protecting ideas across industries from biotech to gaming. This guide explores why patents matter, real-world cases, risks...

Patent infringement is modern-day piracy. Learn how to protect your ideas, enforce your rights, and defend your treasure chest of innovation against IP thieves in...

Patents aren’t just paperwork—they’re a startup’s secret weapon. Learn how to build, manage, and monetize a strong portfolio that attracts investors, protects innovation, and fuels...

Patenting software transforms code into a fortress. Learn how to document, file, and enforce software patents with real-world examples, historical insights, and practical tips for...

Retail & POS tech is transforming the way we shop—from kiosks to smart carts. Discover how patents, trademarks, and copyrights protect innovations that keep your...

Wondering if you need a provisional or non-provisional patent? Discover the key differences, startup strategies, and common pitfalls in patent filing. Learn how to protect...

Unlock effortless passive income by licensing your patents! Discover how entrepreneurs earn royalties while relaxing, the secrets to airtight agreements, and the pitfalls to avoid...

Protect your snacks! Discover how patent strategies can help hungry startups guard their food and beverage inventions, outsmart competitors, and build lasting brand value. Learn...

Patents are your startup’s not-so-secret weapon in fundraising. Learn how combining patents with your pitch deck impresses investors, boosts your valuation, and keeps copycats at...

Discover how unicorn startups protect their wildest ideas using provisional patents and the latest patent law strategies. From actionable steps to expert insights, this article...

Discover the most affordable ways for startups and solo inventors to secure patent protection. Learn about DIY filing, provisional patents, cost-saving tips, and smart strategies—without...

Can you file one patent for multiple inventions? Yes—but beware! The USPTO may require you to split them up, impacting your costs, patent terms, and...

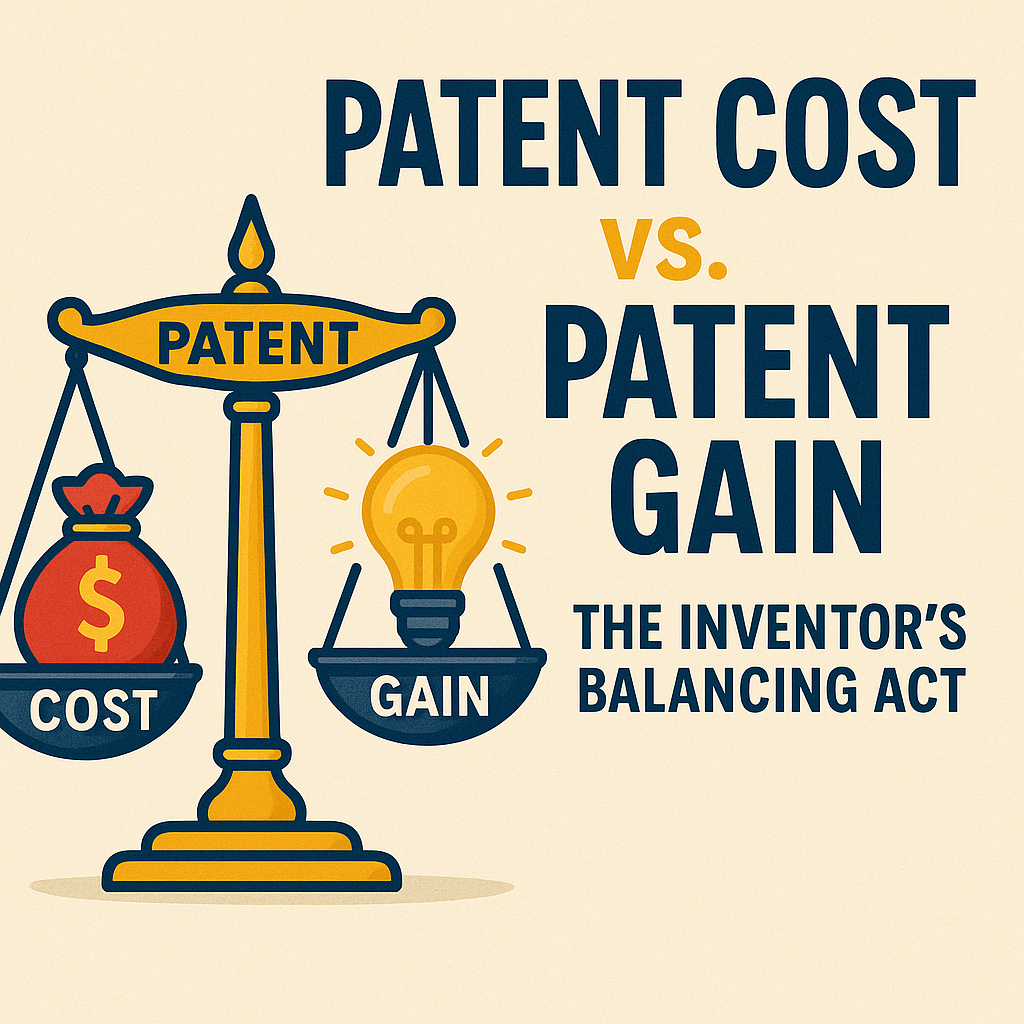

Patents can be gold—or just a gold drain. This guide helps inventors decide when to invest, when to hold back, and how to evaluate if...

Think your invention’s safe just because it solves a different problem? Think again. This article explains why prior art that teaches your solution—even for unrelated...

Tired of your patent application getting rejected with a red pen? If you're arguing it's just "better, faster, cheaper," you're doing it wrong. Learn why...